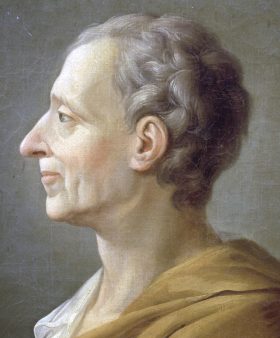

French social commentator and political thinker (1689–1755)

This article is about the French philosopher. For other uses, see Montesquieu (disambiguation).

MontesquieuPortrait by an anonymous artist, c. 1753–1794Born18 January 1689Château de la Brède, La Brède, Aquitaine, FranceDied10 February 1755(1755-02-10) (aged 66)Paris, FranceSpouse

Jeanne de Lartigue (m. 1715)Children3Era18th-century philosophyRegionWestern philosophySchoolEnlightenmentClassical liberalismMain interestsPolitical philosophyNotable ideasSeparation of state powers: executive, legislative, judicial; classification of systems of government based on their principles

Signature

Charles Louis de Secondat, Baron de La Brède et de Montesquieu (French pronunciation: [ʃaʁl lwi də səɡɔ̃da baʁɔ̃ də la bʁɛd e də mɔ̃tɛskjø]; 18 January 1689 – 10 February 1755), generally referred to as simply Montesquieu (US: /ˈmɒntəskjuː/,[1] UK also /ˌmɒntɛˈskjɜː/,[2] French: [mɔ̃tɛskjø]), was a French judge, man of letters, historian, and political philosopher.

He is the principal source of the theory of separation of powers, which is implemented in many constitutions throughout the world. He is also known for doing more than any other author to secure the place of the word despotism in the political lexicon.[3] His anonymously published The Spirit of Law (1748), which was received well in both Great Britain and the American colonies, influenced the Founding Fathers of the United States in drafting the U.S. Constitution.

Biography[edit]

Château de la Brède

Montesquieu was born at the Château de la Brède in southwest France, 25 kilometres (16 mi) south of Bordeaux.[4] His father, Jacques de Secondat (1654–1713), was a soldier with a long noble ancestry, including descent from Richard de la Pole, Yorkist claimant to the English crown. His mother, Marie Françoise de Pesnel (1665–1696), who died when Charles was seven, was an heiress who brought the title of Barony of La Brède to the Secondat family.[5] His family was of Huguenot origin.[6][7] After the death of his mother he was sent to the Catholic College of Juilly, a prominent school for the children of French nobility, where he remained from 1700 to 1711.[8] His father died in 1713 and he became a ward of his uncle, the Baron de Montesquieu.[9] He became a counselor of the Bordeaux Parlement in 1714. He showed preference for Protestantism[10][11] and in 1715 he married the Protestant Jeanne de Lartigue, who eventually bore him three children.[12] The Baron died in 1716, leaving him his fortune as well as his title, and the office of président à mortier in the Bordeaux Parlement,[13] a post that he would hold for twelve years.

Montesquieu's early life was a time of significant governmental change. England had declared itself a constitutional monarchy in the wake of its Glorious Revolution (1688–1689), and joined with Scotland in the Union of 1707 to form the Kingdom of Great Britain. In France, the long-reigning Louis XIV died in 1715 and was succeeded by the five-year-old Louis XV. These national transformations had a great impact on Montesquieu; he would refer to them repeatedly in his work.

Montesquieu's 1748 De l'Esprit des loix

Montesquieu eventually withdrew from the practice of law to devote himself to study and writing. He achieved literary success with the publication of his 1721 Persian Letters (French: Lettres persanes), a satire representing society as seen through the eyes of two Persian visitors to Paris, cleverly criticizing absurdities of contemporary French society. The work was an instant classic and accordingly was immediately pirated. In 1722, he went to Paris and entered social circles with the help friends including the Duke of Berwick whom he had known when Berwick was military governor at Bordeaux. He also acquainted himself with the English politician Viscount Bolingbroke, some of whose political views were later reflected in Montesquieu's analysis of English constitution. In 1726 he sold his office, bored with the parlement and turning more toward Paris. In time, despite some impediments he was elected to the Académie Française in January 1728.

In April 1728, with Berwick's nephew Lord Waldegrave as his traveling companion, Montesquieu embarked on a grand tour of Europe, during which he kept a journal. His travels included Austria and Hungary and a year in Italy. He went to England at the end of October 1729, in the company of Lord Chesterfield, where he was initiated into Freemasonry at the Horn Tavern Lodge in Westminster.[14] He remained in England until the spring of 1731, when he returned to La Brède. Outwardly he seemed to be settling down as a squire: he altered his park in the English fashion, made inquiries into his own genealogy, and asserted his seignorial rights. But he was continuously at work in his study, and his reflections on geography, laws and customs during his travels became the primary sources for his major works on political philosophy at this time.[15] He next published Considerations on the Causes of the Greatness of the Romans and their Decline (1734), among his three best known books. He was to publish The Spirit of Law in 1748, quickly translated into English. It quickly rose to influence political thought profoundly in Europe and America. In France, the book met with an enthusiastic reception by many but was denounced by the Sorbonne and, in 1751, by the Catholic Church (Index of Prohibited Books). It received the highest praise from much of the rest of Europe, especially Britain.

Lettres familières à divers amis d'Italie, 1767

Montesquieu was also highly regarded in the British colonies in North America as a champion of liberty. According to a survey of late eighteenth-century works by political scientist Donald Lutz, Montesquieu was the most frequently quoted authority on government and politics in colonial pre-revolutionary British America, cited more by the American founders than any source except for the Bible.[16] Following the American Revolution, his work remained a powerful influence on many of the American founders, most notably James Madison of Virginia, the "Father of the Constitution". Montesquieu's philosophy that "government should be set up so that no man need be afraid of another"[17] reminded Madison and others that a free and stable foundation for their new national government required a clearly defined and balanced separation of powers.

Montesquieu was troubled by a cataract and feared going blind. At the end of 1754 he visited Paris and was soon taken ill, and died from a fever on 10 February 1755. He was buried in the Église Saint-Sulpice, Paris.

Philosophy of history[edit]

Montesquieu's philosophy of history minimized the role of individual persons and events. He expounded the view in Considerations on the Causes of the Greatness of the Romans and their Decline, that each historical event was driven by a principal movement:

It is not chance that rules the world. Ask the Romans, who had a continuous sequence of successes when they were guided by a certain plan, and an uninterrupted sequence of reverses when they followed another. There are general causes, moral and physical, which act in every monarchy, elevating it, maintaining it, or hurling it to the ground. All accidents are controlled by these causes. And if the chance of one battle—that is, a particular cause—has brought a state to ruin, some general cause made it necessary for that state to perish from a single battle. In a word, the main trend draws with it all particular accidents.[18]

In discussing the transition from the Republic to the Empire, he suggested that if Caesar and Pompey had not worked to usurp the government of the Republic, other men would have risen in their place. The cause was not the ambition of Caesar or Pompey, but the ambition of man.

Political views[edit]

Part of the Politics seriesRepublicanism

Concepts

Anti-monarchism

Democracy

Democratization

Liberty as non-domination

Popular sovereignty

Republic

Res publica

Social contract

Schools

Classical

Modern

Federal

Kemalism

Nasserism

Neo-republicanism

Venizelism

Types

Autonomous

Capitalist

Christian

Democratic

Federal

Federal parliamentary

Islamic

Parliamentary

People's

Revolutionary

Secular

Sister

Soviet

Philosophers

Arendt

Cicero

Harrington

Jefferson

Locke

Machiavelli

Madison

Mazzini

Montesquieu

Pettit

Polybius

Rousseau

Sandel

Sidney

Tocqueville

Wollstonecraft

History

Roman Republic

Gaṇasaṅgha

Classical Athens

Republic of Venice

Republic of Genoa

Republic of Florence

Dutch Republic

American Revolution

French Revolution

Spanish American wars of independence

Trienio Liberal

French Revolution of 1848

5 October 1910 revolution

Chinese Revolution

Russian Revolution

German Revolution of 1918–1919

Turkish War of Independence

Mongolian Revolution of 1921

11 September 1922 Revolution

1935 Greek coup d'état attempt

Spanish Civil War

1946 Italian institutional referendum

1952 Egyptian revolution

14 July Revolution

North Yemen Civil War

Zanzibar Revolution

1969 Libyan coup d'état

1970 Cambodian coup d'état

Metapolitefsi

Iranian Revolution

1987 Fijian coups d'état

Nepalese Civil War

Barbadian Republic Proclamation

National variants

Antigua and Barbuda

Australia

Bahamas

Barbados

Canada

Ireland

Jamaica

Japan

Morocco

Netherlands

New Zealand

Norway

Spain

Sweden

United Kingdom

Scotland

Wales

United States

Related topics

Communitarianism

Criticism of monarchy

Egalitarianism

The Emperor's New Clothes

Liberalism

Monarchism

Primus inter pares

Politics portalvte

This article is part of a series onLiberalism in France

Schools

Classical

Orthodox

Orléanism

Economic

National

Radical

Jacobinism

Social

Principles

Anti-clericalism

Civic nationalism

Civil and political rights

Economic freedom

Equality before the law

Freedom of the press

Freedom of speech

Laicism

Laissez-faire

Liberté, égalité, fraternité

Republicanism

History

Dreyfusards

February Revolution

French Resistance

French Revolution

July Monarchy

July Revolution

Lumières

People

Alain

Aron

Bastiat

Brissot

Clemenceau

de Condorcet

Constant

Doumergue

Fallières

Gambetta

de Gouges

Grévy

Louis Philippe I (early)

Macron

Mendès France

Merleau-Ponty

Montesquieu

Poincaré

Thiers

de Tocqueville

Voltaire

PartiesActive

Agir

Centrist Alliance

The Centrists

Democratic European Force

Democratic Movement

Liberal Alternative

Liberal Democratic Party

Radical Party

Radical Party of the Left

Renaissance

Union of Democrats and Independents

Former

Democratic Republican Alliance

Doctrinaires

Independent Radicals

Jacobins

Girondins

Liberal Party

Moderate Republicans (1848)

Moderate Republicans (1871)

Progressive Republicans

Radical Movement

Republican Union

Union for French Democracy

MediaActive

BFM TV

La Chaîne Info

Courrier International

Les Echos

Le Figaro

Le Monde

L'Opinion

Le Parisien

Former

L'Aurore

Related topics

Centrism in France

Political positions of Emmanuel Macron

Rally of Republican Lefts

Laïcité

Sinistrisme

Together (coalition)

Liberalism portal

France portalvte

Montesquieu is credited as being among the progenitors, who include Herodotus and Tacitus, of anthropology—as being among the first to extend comparative methods of classification to the political forms in human societies. Indeed, the French political anthropologist Georges Balandier considered Montesquieu to be "the initiator of a scientific enterprise that for a time performed the role of cultural and social anthropology".[19] According to social anthropologist D. F. Pocock, Montesquieu's The Spirit of Law was "the first consistent attempt to survey the varieties of human society, to classify and compare them and, within society, to study the inter-functioning of institutions."[20] "Émile Durkheim," notes David W. Carrithers, "even went so far as to suggest that it was precisely this realization of the interrelatedness of social phenomena that brought social science into being."[21] Montesquieu's political anthropology gave rise to his influential view that forms of government are supported by governing principles: virtue for republics, honor for monarchies, and fear for despotisms. American founders studied Montesquieu’s views on how the English achieved liberty by separating executive, legislative, and judicial powers, and when Catherine the Great wrote her Nakaz (Instruction) for the Legislative Assembly she had created to clarify the existing Russian law code, she avowed borrowing heavily from Montesquieu's Spirit of Law, although she discarded or altered portions that did not support Russia's absolutist bureaucratic monarchy.[22]

Montesquieu's most influential work divided French society into three classes (or trias politica, a term he coined): the monarchy, the aristocracy, and the commons.[clarification needed] Montesquieu saw two types of governmental power existing: the sovereign and the administrative. The administrative powers were the executive, the legislative, and the judicial. These should be separate from and dependent upon each other so that the influence of any one power would not be able to exceed that of the other two, either singly or in combination. This was a radical idea because it does not follow the three Estates structure of the French Monarchy: the clergy, the aristocracy, and the people at large represented by the Estates-General, thereby erasing the last vestige of a feudalistic structure.

The theory of the separation of powers largely derives from The Spirit of Law:

In every state there are three kinds of power: the legislative authority, the executive authority for things that stem from the law of nations, and the executive authority for those that stem from civil law.

By virtue of the first, the prince or magistrate enacts temporary or perpetual laws, and amends or abrogates those that have been already enacted. By the second, he makes peace or war, sends or receives embassies, establishes the public security, and provides against invasions. By the third, he punishes criminals, or determines the disputes that arise between individuals. The latter we shall call the judiciary power, and the other, simply, the executive power of the state.

— The Spirit of Law, XI, 6.

Montesquieu argues that each power should only exercise its own functions; he is quite explicit here:

When in the same person or in the same body of magistracy the legislative authority is combined with the executive authority, there is no freedom, because one can fear lest the same monarch or the same senate make tyrannical laws in order to carry them out tyrannically.

Again there is no freedom if the authority to judge is not separated from the legislative and executive authorities. If it were combined with the legislative authority, power over the life and liberty of the citizens would be arbitrary, for the judge would be the legislator. If it were combined with the executive authority, the judge could have the strength of an oppressor.

All would be lost if the same man or the same body of principals, or of nobles, or of the people, exercised these three powers: that of making laws, that of executing public resolutions, and that of judging crimes or disputes between individuals.

— The Spirit of Law, XI, 6.

If the legislative branch appoints the executive and judicial powers, as Montesquieu indicated, there will be no separation or division of its powers, since the power to appoint carries with it the power to revoke.

The executive authority must be in the hands of a monarch, for this part of the government, which almost always requires immediate action, is better administrated by one than by several, whereas that which depends on the legislative authority is often better organized by several than by one person alone.

If there were no monarch, and the executive authority were entrusted to a certain number of persons chosen from the legislative body, that would be the end of freedom, because the two authorities would be combined, the same persons sometimes having, and always in a position to have, a role in both.

— The Spirit of Law, XI, 6.

Montesquieu identifies three main forms of government, each supported by a social "principle": monarchies (free governments headed by a hereditary figure, e.g. king, queen, emperor), which rely on the principle of honor; republics (free governments headed by popularly elected leaders), which rely on the principle of virtue; and despotisms (unfree), headed by despots which rely on fear. The free governments are dependent on constitutional arrangements that establish checks and balances. Montesquieu devotes one chapter of The Spirit of Law to a discussion of how the England's constitution sustained liberty (XI, 6), and another to the realities of English politics (XIX, 27). As for France, the intermediate powers (including the nobility) the nobility and the parlements had been weakened by Louis XIV, and welcomed the strenthening of parlementary power in 1715.

Montesquieu advocated reform of slavery in The Spirit of Law, specifically arguing that slavery was inherently wrong because all humans are born equal,[23] but that it could perhaps be justified within the context of climates with intense heat, wherein laborers would feel less inclined to work voluntarily.[23] As part of his advocacy he presented a satirical hypothetical list of arguments for slavery. In the hypothetical list, he'd ironically list pro-slavery arguments without further comment, including an argument stating that sugar would become too expensive without the free labor of slaves.[23]

While addressing French readers of his General Theory, John Maynard Keynes described Montesquieu as "the real French equivalent of Adam Smith, the greatest of your economists, head and shoulders above the physiocrats in penetration, clear-headedness and good sense (which are the qualities an economist should have)."[24]

Meteorological climate theory[edit]

This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed.Find sources: "Montesquieu" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (January 2020) (Learn how and when to remove this template message)

Another example of Montesquieu's anthropological thinking, outlined in The Spirit of Law and hinted at in Persian Letters, is his meteorological climate theory, which holds that climate may substantially influence the nature of man and his society, a theory also promoted by the French naturalist Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon. By placing an emphasis on environmental influences as a material condition of life, Montesquieu prefigured modern anthropology's concern with the impact of material conditions, such as available energy sources, organized production systems, and technologies, on the growth of complex socio-cultural systems.

He goes so far as to assert that certain climates are more favorable than others, the temperate climate of France being ideal. His view is that people living in very warm countries are "too hot-tempered", while those in northern countries are "icy" or "stiff". The climate of middle Europe is therefore optimal. On this point, Montesquieu may well have been influenced by a similar pronouncement in The Histories of Herodotus, where he makes a distinction between the "ideal" temperate climate of Greece as opposed to the overly cold climate of Scythia and the overly warm climate of Egypt. This was a common belief at the time, and can also be found within the medical writings of Herodotus' times, including the "On Airs, Waters, Places" of the Hippocratic corpus. One can find a similar statement in Germania by Tacitus, one of Montesquieu's favorite authors.

Philip M. Parker, in his book Physioeconomics (MIT Press, 2000), endorses Montesquieu's theory and argues that much of the economic variation between countries is explained by the physiological effect of different climates.

From a sociological perspective, Louis Althusser, in his analysis of Montesquieu's revolution in method,[25] alluded to the seminal character of anthropology's inclusion of material factors, such as climate, in the explanation of social dynamics and political forms. Examples of certain climatic and geographical factors giving rise to increasingly complex social systems include those that were conducive to the rise of agriculture and the domestication of wild plants and animals.

Memorialization[edit]

Between 1981 and 1994, a depiction of Monetesquieu appeared on the 200 French franc note.[26]

Montesquieu on the 200 French franc note

Since 1989, the annual Montesquieu prize has been awarded by the French Association of Historians of Political Ideas for the best French-language thesis on the history of political thought.[27]

On Europe Day 2007, the Montesquieu Institute opened in The Hague, the Netherlands, with a mission to advance research and education on the parliamentary history and political culture of the European Union and its member states.[28]

The Montesquieu tower in Luxembourg was completed in 2008 as an addition to the headquarters of the Court of Justice of the European Union.[29] The building houses many of the institution's translation services. Until 2019, it stood, with its sister tower, Comenius, as the tallest building in the country.[29]

Chronology and principal works[edit]

1689 18 January: Birth of Charles Louis de Secondat at La Brède, son of Jacques de Secondat and Marie Françoise de Pesnel.

1700–1705: Schooling along with two cousins at the Oratorian school in Juilly, near Paris, where he received a classical education.

1705–1708: Study of law in Bordeaux

1709–1713: Residence in Paris.

1713: Death of his father; Montesquieu returns to Bordeaux to assume role as head of family.

1714: Appointed counselor in the parliament of Bordeaux.

1715: Marriage to Jeanne de Lartigue, a Calvinist who brings him a substantial dowry. Spicilège (Gleanings, 1715 onward)

1716: Birth of a son, Jean-Baptiste; death of his uncle, from whom he inherits the title Baron de Montesquieu, and the office of judge (président à mortier) in the parlement. Reception as member of the royal academy in Bordeaux.

1718–1721: Memoirs and discourses at the Academy of Bordeaux (1718–1721): including discourses on such topics as echoes, the renal glands, the weight of bodies, the transparency of bodies, and on natural history, collected with introductions and critical apparatus in volumes 8 and 9 of Œuvres complètes, Oxford and Naples, 2003–2006.

1721: Persian Letters, translated into English the following year by John Ozell.

1725: Treatise on Duties; The Temple of Gnidus, a prose poem; Reflections on the Character of Certain Princes (?); Discourse on Equity; first mention of the Dialogue between Sulla and Eucrates.

1726: Sale of the usufruct of Montesquieu’s parlementary office.

1727: Montesquieu begins a compilation called Mes Pensées (My Thoughts) which he will draw on in various writings for the rest of his life.

1728: Election to the Académie française.

1728 (April)–1729 (Oct.): Travels in Austria, Hungary, Italy, Germany, and Holland (composition of his Travels).

1729 (Nov.) –1731 (spring): Visit to England; composition of Notes on England.

1731–1733: Residence at La Brède.

1734": Considerations on the Causes of the Greatness of the Romans and on their decline; Reflections on Universal Monarchy in Europe; Reflections on the character of certain princes. Montesquieu rents an apartment in the Rue Saint Dominique (faubourg Saint Germain) which he will occupy until his death.

1735–1739: Histoire véritable (True Story); revision of the chapter entitled "On the English Constitution" (The Spirit of Law, XI, 6).

1739–1748: Composition of The Spirit of Law.

1742: First version of Arsace and Ismania, a novel.

1745: Publication of Dialogue between Sulla and Eucrates.

1748 (July): Second edition of Considerations on the Romans; (August) Montesquieu definitively sells his office of président which his son declines to assume; (Nov.) Publication in Geneva of The Spirit of Law.

1749–1751: Battle of The Spirit of Law: (1750) Defense of The Spirit of Law; the Sorbonne (theology faculty) cites 13 propositions in it that should be condemned; (1751) condemnation by the Roman Index.

1750: The Spirit of Laws, English translation of L'Esprit des lois by Thomas Nugent.

1751–1754: Prepares corrections and some additions for Persian Letters, The Spirit of Law, etc.

1755: 10 February: Death in Paris.

1757: Essai sur le goût (Essay on Taste) published in the Encyclopédie.

1758: Posthumous, partially revised edition of his works overseen by his son.

1998– : critical edition of Montesquieu's works published by the Société Montesquieu. As of June 2023, all but five of the planned 22 volumes have appeared.

Works available in English translation[edit]

The Complete Works of M. de Montesquieu, trans. Thomas Nugent, London: T. Evans and W. Davis, 1777, 4 vols. Includes The Spirit of Law, Considerations on […] the Romans, Persian Letters, letters, Essay on Taste, The Temple of Gnidus, Defense of the Spirit of Law. https://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/montesquieu-complete-works-4-vols-1777

The Works of M. de Secondat, baron de Montesquieu, 3 vols., London: Vernor and Hood, 1800. https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/102110886

The Temple of Gnidus with Cephisa and Cupid and Arsaces and Ismenia, trans. John Sayer, London: Vizetelly [1889]. https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/100769287

The Personal and the Political: three fables by Montesquieu (The Temple of Cnidus, Lysimachus, and Dialogue de Sylla et d’Eucrate), bilingual edition by William B. Allen, Lanham: University Press of America, 2008.

Reflections on the Causes of the Rise and Fall of the Roman Empire, fourth edition, Glasgow: Robert Urie, 1758. https://archive.org/details/reflectionsoncau00mont/page/n6

Reflections on the Causes of the Rise and Fall of the Roman Empire, Oxford: Geo. B. Whittaker, 1825. https://archive.org/details/reflectionsonca00montgoog/page/n7

Considerations on the causes of the grandeur and decadence of the Romans, trans. Jehu Baker, New York: D. Appleton, 1882. https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/100769779;

https://archive.org/stream/cu31924028288722#page/n5/mode/2up

Considerations on the Causes of the Greatness of the Romans and their Decline, trans. David Lowenthal, New York: Free Press, 1965; Indianapolis: Hackett, 1999.

Persian Letters (Lettres persanes). There are several English translations, only two of which use the same reference system as the OC edition (based on the original edition of 1721): trans. Margaret Mauldon, Oxford World Classics, 2008, and trans. Philip Stewart, 2020, open access: https://montesquieu.ens-lyon.fr/spip.php?article3494.

The Spirit of Laws, English translation by Thomas Nugent. There were numerous editions (and variations) of this translation published over the next two-plus centuries.

The Spirit of Laws : a compendium of the first English edition, edited, with introduction, notes, and appendixes, by David Wallace Carrithers, with An essay on causes affecting minds and characters, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1977.

The Spirit of the Laws, trans. Anne M. Cohler, Basia C. Miller, and Harold S. Stone, Cambridge University Press, 1989.

The Spirit of Law, trans. Philip Stewart, 2018. Open access: http://montesquieu.ens-lyon.fr/spip.php?rubrique186

My Thoughts (Mes pensées), trans. Henry C. Clark, Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2012. On line:

https://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/montesquieu-my-thoughts-mes-pensees-1720-2012

Discourses, Dissertations, and Dialogues on Science, Politics, and Religion, trans. David Carrithers and Philip Stewart, introduction and notes by David Carrithers, New York: Cambridge University Press, 2020.

General studies in English[edit]

Emile Durkheim, Montesquieu and Rousseau, Forerunners of Sociology, Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1961.

David W. Carrithers and Patrick Coleman (eds.), Montesquieu and the Spirit of Modernity, (SVEC 2002:09), Oxford: Voltaire Foundation.

Rebecca E. Kingston, ed., Montesquieu and His Legacy, Albany: SUNY Press, 2009.

Domenico Felice, Montesquieu: an Introduction, Mila-Udine: Mimesis International, 2018.

Keegan Callanan and Sharon Ruth Krause (eds.), The Cambridge Companion to Montesquieu, Cambridge University Press, 2023.

The Spirit of Law[edit]

Sheila Mason, Montesquieu’s Idea of Justice, The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1975.

Mark Hulliung, Montesquieu and the Old Regime, Berkeley: University of California Press,

1976.

Stephen J. Rosow, "Commerce, Power and Justice: Montesquieu on international politics", Review of Politics 46, no. 3 (July 1984): 346–366.

Anne M. Cohler, Montesquieu’s Comparative Politics and the Spirit of American Constitutionalism, Lawrence KS: University Press of Kansas, 1988.

Thomas L. Pangle, Montesquieu’s Philosophy of Liberalism: a commentary on "The Spirit of the Laws", Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1989.

David W. Carrithers, "Montesquieu’s philosophy of punishment", History of Political Thought 19 (1998), p. 213-240.

David W. Carrithers, Michael A. Mosher, and Paul A. Rahe, eds., Montesquieu’s Science of Politics: essays on "The Spirit of Laws", Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield, 2001.

Robert Howse, "Montesquieu on Commerce, War, and Peace", Brookings Journal of International Law 31, no. 3 (2006): 693–708.

Paul A. Rahe, Montesquieu and the Logic of Liberty, New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009.

Andrea Radasanu, "Montesquieu on Moderation, Monarchy and Reform", History of Political Thought 31, no. 2 (2010): 283–307.

Rolando Minuti, Studies on Montesquieu: mapping political diversity, Cham (Switzerland): Springer, 2018. (Translation by Julia Weiss of Una geografia politica della diversità: studi su Montesquieu, Naples, Liguori, 2015.)

Andrew Scott Bibby, Montesquieu’s Political Economy, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016.

Joshua Bandoch, The Politics of Place: Montesquieu, particularism, and the pursuit of liberty, Rochester: University of Rochester Press, 2017.

Vickie B. Sullivan, Montesquieu and the Despotic Ideas of Europe: an interpretation of "The Spirit of the laws", University of Chicago Press, 2017.

Keegan Callanan, Montesquieu’s Liberalism and the Problem of Universal Politics, New York: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

Sharon R. Krause, The Rule of Law in Montesquieu, Cambridge University Press, 2021.

Vicki V. Sullivan, "Montesquieu on Slavery" in K. Callanan, The Cambridge Companion to Montesquieu, p. 182-197.

See also[edit]

Environmental determinism

Liberalism

List of abolitionist forerunners

List of political systems in France

List of liberal theorists

Napoleon

Politics of France

Jean-Baptiste de Secondat (1716–1796), his son

U.S. Constitution, influences

Bibliography of the United States Constitution — Contains numerous works regarding Montesqui's influence on American constitutionalism.

Portals: Philosophy Law France

References[edit]

Notes[edit]

^ "Montesquieu" Archived 21 November 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

^ Wells, John C. (2008). Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.). Longman. ISBN 978-1-4058-8118-0.

^ Boesche 1990, p. 1.

^ "Bordeaux · France". Bordeaux · France.

^ Sorel, A. Montesquieu. London, George Routledge & Sons, 1887 (Ulan Press reprint, 2011), p. 10. ASIN B00A5TMPHC

^ Enlightenment Contested: Philosophy, Modernity, and the Emancipation of Man 1670-1752. OUP Oxford. 12 October 2006. ISBN 978-0-19-927922-7.

^ Agreeable Connexions: Scottish Enlightenment Links with France. Casemate Publishers. 5 November 2012. ISBN 9781907909085.

^ Sorel (1887), p. 11.

^ Sorel (1887), p. 12.

^ Montesquieu's Liberalism and the Problem of Universal Politics. Cambridge University Press. 23 August 2018. ISBN 9781108552691.

^ Civil Religion: A Dialogue in the History of Political Philosophy. Cambridge University Press. 25 October 2010. ISBN 9781139492614.

^ Sorel (1887), pp. 11–12.

^ Sorel (1887), pp. 12–13.

^ Berman 2012, p. 150

^ Li, Hansong (25 September 2018). "The space of the sea in Montesquieu's political thought". Global Intellectual History. 6 (4): 421–442. doi:10.1080/23801883.2018.1527184. S2CID 158285235.

^ Lutz 1984.

^ Montesquieu, The Spirit of Law, Book 11, Chapter 6, "On the English Constitution." Archived 28 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine Electronic Text Center, University of Virginia Library, Retrieved 1 August 2012

^ Montesquieu (1734), Considerations on the Causes of the Greatness of the Romans and their Decline, The Free Press, archived from the original on 6 August 2010, retrieved 30 November 2011 Ch. XVIII.

^ Balandier 1970, p. 3.

^ Pocock 1961, p. 9.Tomaselli 2006, p. 9, similarly describes it as "among the most intellectually challenging and inspired contributions to political theory in the eighteenth century. [... It] set the tone and form of modern social and political thought."

^ Carrithers, 1977, p. 27, citing Durkheim 1960, pp. 56–57)

^ Ransel 1975, p. 179.

^ a b c Mander, Jenny. 2019. "Colonialism and Slavery". p. 273 in The Cambridge History of French Thought, edited by M. Moriarty and J. Jennings. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

^ See the preface Archived 10 November 2014 at the Wayback Machine to the French edition of Keynes' General Theory.See also Devletoglou 1963.

^ Althusser 1972.

^ "200 Francs Montesquieu | Grand choix de billets de collection de la BDF". Bourse du collectionneur (in French). Retrieved 1 October 2023.

^ "Prix Montesquieu - Association Française des Historiens des idées politiques". univ-droit.fr : Portail Universitaire du droit (in French). Retrieved 1 October 2023.

^ "Start Montesquieu Instituut". www.montesquieu-instituut.nl (in Dutch). Retrieved 1 October 2023.

^ a b "Montesquieu Tower". Europa (web portal). Retrieved 1 October 2023.

Sources[edit]

Articles and chapters

Boesche, Roger (1990). "Fearing Monarchs and Merchants: Montesquieu's Two Theories of Despotism". The Western Political Quarterly. 43 (4): 741–761. doi:10.1177/106591299004300405. JSTOR 448734. S2CID 154059320.

Devletoglou, Nicos E. (1963). "Montesquieu and the Wealth of Nations". The Canadian Journal of Economics and Political Science. 29 (1): 1–25. doi:10.2307/139366. JSTOR 139366.

Kuznicki, Jason (2008). "Montesquieu, Charles de Second de (1689–1755)". In Hamowy, Ronald (ed.). Knight, Frank H. (1885–1972). The Encyclopedia of Libertarianism. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; Cato Institute. pp. 341–342. doi:10.4135/9781412965811.n164. ISBN 978-1412965804. LCCN 2008009151. OCLC 750831024.

Lutz, Donald S. (1984). "The Relative Influence of European Writers on Late Eighteenth-Century American Political Thought". American Political Science Review. 78 (1): 189–197. doi:10.2307/1961257. JSTOR 1961257. S2CID 145253561.

Tomaselli, Sylvana. "The spirit of nations". In Mark Goldie and Robert Wokler, eds., The Cambridge History of Eighteenth-Century Political Thought (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006). pp. 9–39.

Books

Althusser, Louis, Politics and History: Montesquieu, Rousseau, Marx (London and New York: New Left Books, 1972).

Balandier, Georges, Political Anthropology (London: Allen Lane, 1970).

Berman, Ric (2012), The Foundations of Modern Freemasonry: The Grand Architects – Political Change and the Scientific Enlightenment, 1714–1740 (Eastbourne: Sussex Academic Press, 2012).

Pocock, D. F., Social Anthropology (London and New York: Sheed and Ward, 1961).

Ransel, David L., The Politics of Catherinian Russia: The Panin Party (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1975).

Shackleton, Robert, Montesquieu: a Critical Biography (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1961).

Shklar, Judith, Montesquieu (Oxford Past Masters series). (Oxford and New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1989).

Spurlin, Paul M., Montesquieu in America, 1760–1801 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1941; reprint, New York: Octagon Books, 1961).

Volpilhac-Auger, Catherine, Montesquieu (Folio Bibliographies) (Paris: Gallimard, 2017). Montesquieu: Let there be Enlightenment, English translation by Philip Stewart, Cambridge University Press, 2023.

External links[edit]

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Montesquieu.

Wikiquote has quotations related to Montesquieu.

Wikisource has original works by or about:Montesquieu

Société Montesquieu, [1]

A Montesquieu Dictionary, on line: "[2] Archived 27 February 2022 at the Wayback Machine"

Ilbert, Courtenay (1913). "Montesquieu". In Macdonell, John; Manson, Edward William Donoghue (eds.). Great Jurists of the World. London: John Murray. pp. 1–16. Retrieved 14 February 2019 – via Internet Archive.

Works by Montesquieu at Project Gutenberg

Works by or about Montesquieu at Internet Archive

Works by Montesquieu at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

Free full-text works online

The Spirit of Laws (Volume 1) Audio book of Thomas Nugent translation

[3] Archived 27 February 2022 at the Wayback Machine The Spirit of Law, trans. Philip Stewart, open access.

[4] Archived 13 December 2020 at the Wayback Machine Persian Letters, trans. Philip Stewart, open access.

Complete ebooks collection of Montesquieu in French.

Lettres persanes at athena.unige.ch (in French)

Montesquieu, "Notes on England"

Montesquieu in The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

"Montesquieu", Institut d'histoire des représentations et des idées dans les modernités (in French)

Links to related articles

vteAcadémie française seat 2

Valentin Conrart (1634)

Toussaint Rose (1675)

Louis de Sacy (1701)

Charles de Secondat, baron de Montesquieu (1728)

Jean-Baptiste Vivien de Châteaubrun (1755)

François-Jean de Chastellux (1775)

Aimar-Charles-Marie de Nicolaï (1788)

François de Neufchâteau (1803)

Pierre-Antoine Lebrun (1828)

Alexandre Dumas fils (1874)

André Theuriet (1896)

Jean Richepin (1908)

Émile Mâle (1927)

François Albert-Buisson (1955)

Marc Boegner (1962)

René de Castries (1972)

André Frossard (1987)

Hector Bianciotti (1996)

Dany Laferrière (2013)

vteAge of EnlightenmentTopics

Atheism

Capitalism

Civil liberties

Classicism

Counter-Enlightenment

Critical thinking

Deism

Democracy

Empiricism

Encyclopédistes

Enlightened absolutism

Haskalah

Humanism

Human rights

Individualism

Liberalism

Liberté, égalité, fraternité

Lumières

Methodological skepticism

Midlands

Modernity

Natural philosophy

Objectivity

Progressivism

Rationality

Rationalism

Reason

Reductionism

Sapere aude

Science

Scientific method

Spanish America

Universality

Utopianism

ThinkersEngland

Addison

Ashley-Cooper

Bacon

Bentham

Collins

Gibbon

Godwin

Harrington

Hooke

Johnson

Locke

Milton

Newton

Pope

Price

Priestley

Reynolds

Sidney

Tindal

Wollstonecraft

France

d'Alembert

d'Argenson

Bayle

Beaumarchais

Chamfort

Châtelet

Condillac

Condorcet

Descartes

Diderot

Fontenelle

Gouges

Helvétius

d'Holbach

Jaucourt

La Mettrie

Lavoisier

Leclerc

Mably

Maréchal

Meslier

Montesquieu

Morelly

Pascal

Quesnay

Raynal

Sade

Turgot

Voltaire

Geneva

Abauzit

Bonnet

Burlamaqui

Prévost

Rousseau

Saussure

Germany

Goethe

Herder

Humboldt

Kant

Leibniz

Lessing

Lichtenberg

Mendelssohn

Pufendorf

Schiller

Thomasius

Weishaupt

Wieland

Wolff

Greece

Farmakidis

Feraios

Kairis

Korais

Ireland

Berkeley

Boyle

Burke

Swift

Toland

Italy

Beccaria

Galiani

Galvani

Genovesi

Pagano

Verri

Vico

Netherlands

Bekker

Grotius

Huygens

Leeuwenhoek

Nieuwentyt

Spinoza

Swammerdam

Poland

Kołłątaj

Konarski

Krasicki

Niemcewicz

Poniatowski

Śniadecki

Staszic

Wybicki

Portugal

Carvalho e Melo

Romania

Budai-Deleanu

Maior

Micu-Klein

Șincai

Russia

Catherine II

Fonvizin

Kantemir

Kheraskov

Lomonosov

Novikov

Radishchev

Vorontsova-Dashkova

Serbia

Obradović

Mrazović

Spain

Cadalso

Charles III

Feijóo y Montenegro

Moratín

Jovellanos

Villarroel

Scotland

Beattie

Black

Blair

Boswell

Burnett

Burns

Cullen

Ferguson

Hume

Hutcheson

Hutton

Mill

Newton

Playfair

Reid

Smith

Stewart

United States

Franklin

Jefferson

Madison

Mason

Paine

Romanticism →

Category

vteFrench Revolution

Causes

Timeline

Ancien Régime

Revolution

Constitutional monarchy

Republic

Directory

Consulate

Glossary

Journals

Museum

Significant civil and political events by year1788

Day of the Tiles (7 Jun 1788)

Assembly of Vizille (21 Jul 1788)

1789

What Is the Third Estate? (Jan 1789)

Réveillon riots (28 Apr 1789)

Convocation of the Estates General (5 May 1789)

Death of the Dauphin (4 June 1789)

National Assembly (17 Jun – 9 Jul 1790)

Tennis Court Oath (20 Jun 1789)

National Constituent Assembly (9 Jul – 30 Sep 1791)

Storming of the Bastille (14 Jul 1789)

Great Fear (20 Jul – 5 Aug 1789)

Abolition of Feudalism (4–11 Aug 1789)

Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (26 Aug 1789)

Women's March on Versailles (5 Oct 1789)

Nationalization of the Church properties (2 Nov 1789)

1790

Abolition of the Parlements (Feb–Jul 1790)

Abolition of the Nobility (23 Jun 1790)

Civil Constitution of the Clergy (12 Jul 1790)

Fête de la Fédération (14 Jul 1790)

1791

Flight to Varennes (20–21 Jun 1791)

Champ de Mars massacre (17 Jul 1791)

Declaration of Pillnitz (27 Aug 1791)

The Constitution of 1791 (3 Sep 1791)

National Legislative Assembly (1 Oct 1791 – Sep 1792)

1792

France declares war (20 Apr 1792)

Brunswick Manifesto (25 Jul 1792)

Paris Commune becomes insurrectionary (Jun 1792)

10th of August (10 Aug 1792)

September Massacres (Sep 1792)

National Convention (20 Sep 1792 – 26 Oct 1795)

First republic declared (22 Sep 1792)

1793

Execution of Louis XVI (21 Jan 1793)

Revolutionary Tribunal (9 Mar 1793 – 31 May 1795)

Reign of Terror (27 Jun 1793 – 27 Jul 1794)

Committee of Public Safety

Committee of General Security

Fall of the Girondists (2 Jun 1793)

Assassination of Marat (13 Jul 1793)

Levée en masse (23 Aug 1793)

The Death of Marat (painting)

Law of Suspects (17 Sep 1793)

Marie Antoinette is guillotined (16 Oct 1793)

Anti-clerical laws (throughout the year)

1794

Danton and Desmoulins guillotined (5 Apr 1794)

Law of 22 Prairial (10 Jun 1794)

Thermidorian Reaction (27 Jul 1794)

Robespierre guillotined (28 Jul 1794)

White Terror (Fall 1794)

Closing of the Jacobin Club (11 Nov 1794)

1795–6

Insurrection of 12 Germinal Year III (1 Apr 1795)

Constitution of the Year III (22 Aug 1795)

Directoire (1795–99)

Council of Five Hundred

Council of Ancients

13 Vendémiaire 5 Oct 1795

Conspiracy of the Equals (May 1796)

1797

Coup of 18 Fructidor (4 Sep 1797)

Second Congress of Rastatt (Dec 1797)

1798

Law of 22 Floréal Year VI (11 May 1798)

1799

Coup of 30 Prairial VII (18 Jun 1799)

Coup of 18 Brumaire (9 Nov 1799)

Constitution of the Year VIII (24 Dec 1799)

Consulate

Revolutionary campaigns1792

Verdun

Thionville

Valmy

Royalist Revolts

Chouannerie

Vendée

Dauphiné

Lille

Siege of Mainz

Jemappes

Namur [fr]

1793

First Coalition

War in the Vendée

Battle of Neerwinden)

Battle of Famars (23 May 1793)

Expedition to Sardinia (21 Dec 1792 - 25 May 1793)

Battle of Kaiserslautern

Siege of Mainz

Battle of Wattignies

Battle of Hondschoote

Siege of Bellegarde

Battle of Peyrestortes (Pyrenees)

Siege of Toulon (18 Sep – 18 Dec 1793)

First Battle of Wissembourg (13 Oct 1793)

Battle of Truillas (Pyrenees)

Second Battle of Wissembourg (26–27 Dec 1793)

1794

Battle of Villers-en-Cauchies (24 Apr 1794)

Second Battle of Boulou (Pyrenees) (30 Apr – 1 May 1794)

Battle of Tourcoing (18 May 1794)

Battle of Tournay (22 May 1794)

Glorious First of June (1 Jun 1794)

Battle of Fleurus (26 Jun 1794)

Chouannerie

Battle of Aldenhoven (2 Oct 1794)

Siege of Luxembourg (22 Nov 1794 - 7 Jun 1795)

1795

Siege of Luxembourg (22 Nov 1794 - 7 Jun 1795)

Peace of Basel

1796

Battle of Lonato (3–4 Aug 1796)

Battle of Castiglione (5 Aug 1796)

Battle of Theiningen

Battle of Neresheim (11 Aug 1796)

Battle of Amberg (24 Aug 1796)

Battle of Würzburg (3 Sep 1796)

Battle of Rovereto (4 Sep 1796)

First Battle of Bassano (8 Sep 1796)

Battle of Emmendingen (19 Oct 1796)

Battle of Schliengen (26 Oct 1796)

Second Battle of Bassano (6 Nov 1796)

Battle of Calliano (6–7 Nov 1796)

Battle of Arcole (15–17 Nov 1796)

Ireland expedition (Dec 1796)

1797

Naval Engagement off Brittany (13 Jan 1797)

Battle of Rivoli (14–15 Jan 1797)

Battle of the Bay of Cádiz (25 Jan 1797)

Treaty of Leoben (17 Apr 1797)

Battle of Neuwied (18 Apr 1797)

Treaty of Campo Formio (17 Oct 1797)

1798

French invasion of Switzerland (28 January – 17 May 1798)

French Invasion of Egypt (1798–1801)

Irish Rebellion of 1798 (23 May – 23 Sep 1798)

Quasi-War (1798–1800)

Peasants' War (12 Oct – 5 Dec 1798)

1799

Second Coalition (1798–1802)

Siege of Acre (20 Mar – 21 May 1799)

Battle of Ostrach (20–21 Mar 1799)

Battle of Stockach (25 Mar 1799)

Battle of Magnano (5 Apr 1799)

Battle of Cassano (27–28 Apr 1799)

First Battle of Zurich (4–7 Jun 1799)

Battle of Trebbia (17–20 Jun 1799)

Battle of Novi (15 Aug 1799)

Second Battle of Zurich (25–26 Sep 1799)

1800

Battle of Marengo (14 Jun 1800)

Convention of Alessandria (15 Jun 1800)

Battle of Hohenlinden (3 Dec 1800)

League of Armed Neutrality (1800–02)

1801

Treaty of Lunéville (9 Feb 1801)

Treaty of Florence (18 Mar 1801)

Algeciras campaign (8 Jul 1801)

1802

Treaty of Amiens (25 Mar 1802)

Treaty of Paris (25 Jun 1802)

Military leaders FranceFrench Army

Eustache Charles d'Aoust

Pierre Augereau

Alexandre de Beauharnais

Jean-Baptiste Bernadotte

Louis-Alexandre Berthier

Jean-Baptiste Bessières

Guillaume Brune

Jean François Carteaux

Jean-Étienne Championnet

Chapuis de Tourville

Adam Philippe, Comte de Custine

Louis-Nicolas Davout

Louis Desaix

Jacques François Dugommier

Thomas-Alexandre Dumas

Charles François Dumouriez

Pierre Marie Barthélemy Ferino

Louis-Charles de Flers

Paul Grenier

Emmanuel de Grouchy

Jacques Maurice Hatry

Lazare Hoche

Jean-Baptiste Jourdan

François Christophe de Kellermann

Jean-Baptiste Kléber

Pierre Choderlos de Laclos

Jean Lannes

Charles Leclerc

Claude Lecourbe

François Joseph Lefebvre

Étienne Macdonald

Jean-Antoine Marbot

Marcellin Marbot

François Séverin Marceau

Auguste de Marmont

André Masséna

Bon-Adrien Jeannot de Moncey

Jean Victor Marie Moreau

Édouard Mortier, Duke of Trévise

Joachim Murat

Michel Ney

Pierre-Jacques Osten [fr]

Nicolas Oudinot

Catherine-Dominique de Pérignon

Jean-Charles Pichegru

Józef Poniatowski

Laurent de Gouvion Saint-Cyr

Barthélemy Louis Joseph Schérer

Jean-Mathieu-Philibert Sérurier

Joseph Souham

Jean-de-Dieu Soult

Louis-Gabriel Suchet

Belgrand de Vaubois

Claude Victor-Perrin, Duc de Belluno

French Navy

Charles-Alexandre Linois

Opposition Austria

József Alvinczi

Archduke Charles, Duke of Teschen

Count of Clerfayt (Walloon)

Karl Aloys zu Fürstenberg

Friedrich Freiherr von Hotze (Swiss)

Friedrich Adolf, Count von Kalckreuth

Pál Kray (Hungarian)

Charles Eugene, Prince of Lambesc (French)

Maximilian Baillet de Latour (Walloon)

Karl Mack von Leiberich

Rudolf Ritter von Otto (Saxon)

Prince Josias of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld

Peter Vitus von Quosdanovich

Prince Heinrich XV of Reuss-Plauen

Johann Mészáros von Szoboszló (Hungarian)

Karl Philipp Sebottendorf

Dagobert von Wurmser

Britain

Sir Ralph Abercromby

James Saumarez, 1st Baron de Saumarez

Edward Pellew, 1st Viscount Exmouth

Prince Frederick, Duke of York and Albany

Netherlands

William V, Prince of Orange

Prussia

Charles William Ferdinand, Duke of Brunswick

Frederick Louis, Prince of Hohenlohe-Ingelfingen

Russia

Alexander Korsakov

Alexander Suvorov

Andrei Rosenberg

Spain

Luis Firmin de Carvajal

Antonio Ricardos

Other significant figures and factionsPatriotic Society of 1789

Jean Sylvain Bailly

Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette

François Alexandre Frédéric, duc de la Rochefoucauld-Liancourt

Isaac René Guy le Chapelier

Honoré Gabriel Riqueti, comte de Mirabeau

Emmanuel Joseph Sieyès

Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord

Nicolas de Condorcet

Feuillantsand monarchiens

Grace Elliott

Arnaud de La Porte

Jean-Sifrein Maury

François-Marie, marquis de Barthélemy

Guillaume-Mathieu Dumas

Antoine Barnave

Lafayette

Alexandre-Théodore-Victor, comte de Lameth

Charles Malo François Lameth

André Chénier

Jean-François Rewbell

Camille Jordan

Madame de Staël

Boissy d'Anglas

Jean-Charles Pichegru

Pierre Paul Royer-Collard

Bertrand Barère de Vieuzac

Girondins

Jacques Pierre Brissot

Jean-Marie Roland de la Platière

Madame Roland

Father Henri Grégoire

Étienne Clavière

Marquis de Condorcet

Charlotte Corday

Marie Jean Hérault

Jean Baptiste Treilhard

Pierre Victurnien Vergniaud

Jérôme Pétion de Villeneuve

Jean Debry

Olympe de Gouges

Jean-Baptiste Robert Lindet

Louis Marie de La Révellière-Lépeaux

The Plain

Abbé Sieyès

de Cambacérès

Charles-François Lebrun

Pierre-Joseph Cambon

Bertrand Barère

Lazare Nicolas Marguerite Carnot

Philippe Égalité

Louis Philippe I

Mirabeau

Antoine Christophe Merlin de Thionville

Jean Joseph Mounier

Pierre Samuel du Pont de Nemours

François de Neufchâteau

Montagnards

Maximilien Robespierre

Georges Danton

Jean-Paul Marat

Camille Desmoulins

Louis Antoine de Saint-Just

Paul Barras

Louis Philippe I

Louis Michel le Peletier de Saint-Fargeau

Jacques-Louis David

Marquis de Sade

Georges Couthon

Roger Ducos

Jean-Marie Collot d'Herbois

Jean-Henri Voulland

Philippe-Antoine Merlin de Douai

Antoine Quentin Fouquier-Tinville

Philippe-François-Joseph Le Bas

Marc-Guillaume Alexis Vadier

Jean-Pierre-André Amar

Prieur de la Côte-d'Or

Prieur de la Marne

Gilbert Romme

Jean Bon Saint-André

Jean-Lambert Tallien

Pierre Louis Prieur

Antoine Christophe Saliceti

Hébertistsand Enragés

Jacques Hébert

Jacques-Nicolas Billaud-Varenne

Pierre Gaspard Chaumette

Charles-Philippe Ronsin

Antoine-François Momoro

François-Nicolas Vincent

François Chabot

Jean Baptiste Noël Bouchotte

Jean-Baptiste-Joseph Gobel

François Hanriot

Jacques Roux

Stanislas-Marie Maillard

Charles-Philippe Ronsin

Jean-François Varlet

Theophile Leclerc

Claire Lacombe

Pauline Léon

Gracchus Babeuf

Sylvain Maréchal

OthersFigures

Charles X

Louis XVI

Louis XVII

Louis XVIII

Louis Antoine, Duke of Enghien

Louis Henri, Prince of Condé

Louis Joseph, Prince of Condé

Marie Antoinette

Napoléon Bonaparte

Lucien Bonaparte

Joseph Bonaparte

Joseph Fesch

Joséphine de Beauharnais

Joachim Murat

Jean Sylvain Bailly

Jacques-Donatien Le Ray

Guillaume-Chrétien de Malesherbes

Talleyrand

Thérésa Tallien

Gui-Jean-Baptiste Target

Catherine Théot

Madame de Lamballe

Madame du Barry

Louis de Breteuil

de Chateaubriand

Jean Chouan

Loménie de Brienne

Charles Alexandre de Calonne

Jacques Necker

Jean-Jacques Duval d'Eprémesnil

List of people associated with the French Revolution

Factions

Jacobins

Cordeliers

Panthéon Club

Social Club

Influential thinkers

Les Lumières

Beaumarchais

Edmund Burke

Anacharsis Cloots

Charles-Augustin de Coulomb

Pierre Claude François Daunou

Diderot

Benjamin Franklin

Thomas Jefferson

Antoine Lavoisier

Montesquieu

Thomas Paine

Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Abbé Sieyès

Voltaire

Mary Wollstonecraft

Cultural impact

La Marseillaise

Cockade of France

Flag of France

Liberté, égalité, fraternité

Marianne

Bastille Day

Panthéon

French Republican calendar

Metric system

Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen

Cult of the Supreme Being

Cult of Reason

Temple of Reason

Sans-culottes

Phrygian cap

Women in the French Revolution

Incroyables and merveilleuses

Symbolism in the French Revolution

Historiography of the French Revolution

Influence of the French Revolution

Films

vtePolitical philosophyTerms

Authority

Citizenship

Duty

Elite

Emancipation

Freedom

Government

Hegemony

Hierarchy

Justice

Law

Legitimacy

Liberty

Monopoly

Nation

Obedience

Peace

Pluralism

Power

Progress

Propaganda

Property

Revolution

Rights

Ruling class

Society

Sovereignty

State

Utopia

War

Government

Aristocracy

Autocracy

Bureaucracy

Dictatorship

Democracy

Meritocracy

Monarchy

Oligarchy

Plutocracy

Technocracy

Theocracy

Ideologies

Agrarianism

Anarchism

Capitalism

Christian democracy

Colonialism

Communism

Communitarianism

Confucianism

Conservatism

Corporatism

Distributism

Environmentalism

Fascism

Feminism

Feudalism

Imperialism

Islamism

Liberalism

Libertarianism

Localism

Marxism

Monarchism

Multiculturalism

Nationalism

Nazism

Populism

Republicanism

Social Darwinism

Social democracy

Socialism

Third Way

Concepts

Balance of power

Bellum omnium contra omnes

Body politic

Clash of civilizations

Common good

Consent of the governed

Divine right of kings

Family as a model for the state

Monopoly on violence

Natural law

Negative and positive rights

Night-watchman state

Noble lie

Noblesse oblige

Open society

Ordered liberty

Original position

Overton window

Separation of powers

Social contract

State of nature

Statolatry

Tyranny of the majority

PhilosophersAncient

Aristotle

Chanakya

Cicero

Confucius

Han Fei

Lactantius

Mencius

Mozi

Plato

political philosophy

Polybius

Shang

Sun Tzu

Thucydides

Xenophon

Medieval

Alpharabius

Aquinas

Averroes

Bruni

Dante

Gelasius

al-Ghazali

Ibn Khaldun

Marsilius

Muhammad

Nizam al-Mulk

Ockham

Plethon

Wang

Early modern

Boétie

Bodin

Bossuet

Calvin

Campanella

Filmer

Grotius

Guicciardini

Hobbes

political philosophy

James

Leibniz

Locke

Luther

Machiavelli

Milton

More

Müntzer

Pufendorf

Spinoza

Suárez

18th and 19thcenturies

Bakunin

Bastiat

Beccaria

Bentham

Bolingbroke

Bonald

Burke

Carlyle

Comte

Condorcet

Constant

Cortés

Engels

Fichte

Fourier

Franklin

Godwin

Haller

Hegel

Herder

Hume

Iqbal

political philosophy

Jefferson

Kant

political philosophy

Le Bon

Le Play

Madison

Maistre

Marx

Mazzini

Mill

Montesquieu

Nietzsche

Owen

Paine

Renan

Rousseau

Sade

Saint-Simon

Smith

Spencer

de Staël

Stirner

Taine

Thoreau

Tocqueville

Tucker

Voltaire

20th and 21stcenturies

Agamben

Ambedkar

Arendt

Aron

Badiou

Bauman

Benoist

Berlin

Bernstein

Burnham

Chomsky

Dmowski

Du Bois

Dugin

Dworkin

Evola

Foucault

Fromm

Fukuyama

Gandhi

Gentile

Gramsci

Guénon

Habermas

Hayek

Hoppe

Huntington

Kautsky

Kirk

Kropotkin

Laclau

Lenin

Luxemburg

Mansfield

Mao

Marcuse

Maurras

Michels

Mises

Mosca

Mouffe

Negri

Nozick

Nussbaum

Oakeshott

Ortega

Pareto

Popper

Qutb

Rand

Rawls

Röpke

Rothbard

Russell

Sartre

Schmitt

Scruton

Shariati

Sorel

Spann

Spengler

Strauss

Sun

Taylor

Voegelin

Walzer

Weber

Works

Republic (c. 375 BC)

Politics (c. 350 BC)

De re publica (51 BC)

Treatise on Law (c. 1274)

Monarchia (1313)

The Prince (1532)

Leviathan (1651)

Two Treatises of Government (1689)

The Spirit of Law (1748)

The Social Contract (1762)

Reflections on the Revolution in France (1790)

Rights of Man (1791)

Elements of the Philosophy of Right (1820)

Democracy in America (1835–1840)

The Communist Manifesto (1848)

On Liberty (1859)

The Revolt of the Masses (1929)

The Road to Serfdom (1944)

The Open Society and Its Enemies (1945)

The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951)

A Theory of Justice (1971)

The End of History and the Last Man (1992)

Related

Authoritarianism

Collectivism and individualism

Conflict theories

Contractualism

Critique of political economy

Egalitarianism

Elite theory

Elitism

Institutional discrimination

Jurisprudence

Justification for the state

Philosophy of law

Political ethics

Political spectrum

Left-wing politics

Centrism

Right-wing politics

Separation of church and state

Separatism

Social justice

Statism

Totalitarianism

Index

Category:Political philosophy

vteLiberalismIdeas

Consent of the governed

Due process

Democracy

Economic liberalism

Economic globalization

Equality

Gender

Legal

Federalism

Freedom

Economic

Market

Trade

Press

Religion

Speech

Harm principle

Internationalism

Invisible hand

Labor theory of property

Laissez-faire

Liberty

Negative

Positive

Limited government

Market economy

Natural monopoly

Open society

Permissive society

Popular sovereignty

Property

Private

Public

Rights

Civil and political

Natural and legal

To own property

To bear arms

Rule of law

Secularism

Secular humanism

Separation of church and state

Separation of powers

Social contract

Social justice

Social services

Welfare state

State of natureSchoolsClassical

Economic

Fiscal

Neo

Equity feminism

Georgist

Radical

Anti-clerical

Civic nationalism

Republican

Utilitarian

Whig

Physiocratic

Encyclopaedist

Conservative

Democratic

Liberal conservatism

National

Ordo

Social

Green

Liberal feminism

Ecofeminism

Liberal socialism

Social democracy

Progressivism

Third Way

Other

Constitutional

Constitutional patriotism

Cultural

Corporate

International

Libertarianism

Left-libertarianism

Geolibertarianism

Neoclassical liberalism

Paleolibertarianism

Right-libertarianism

Radical centrism

Religious

Christian

Islamic

Secular

Techno

By regionAfrica

Egypt

Nigeria

Senegal

South Africa

Tunisia

Zimbabwe

Asia

China

Hong Kong

India

Iran

Israel

Japan

South Korea

Anti-Chinilpa

Centrist reformist

Progressive

Philippines

Turkey

Europe

Albania

Armenia

Austria

Belgium

Bulgaria

Croatia

Cyprus

Czech lands

Denmark

Estonia

Finland

France

Orléanist

Georgia

Germany

Greece

Hungary

Italy

Berlusconism

Liberism

Latvia

Lithuania

Luxembourg

Macedonia

Moldova

Montenegro

Netherlands

Norway

Portugal

Romania

Russia

Serbia

Slovakia

Slovenia

Spain

Sweden

Switzerland

Turkey

Ukraine

United Kingdom

Gladstonian

Libertarian

Manchester

Muscular

Radical

Whiggist

Latin America andthe Caribbean

Bolivia

Brazil

Lulism

Chile

Colombia

Cuba

Ecuador

Honduras

Mexico

Nicaragua

Panama

Paraguay

Peru

Uruguay

North America

Canada

United States

Jacksonian

Jeffersonian

Libertarian

Modern

Progressive

Oceania

Australia

Small-l

New Zealand

Philosophers

Milton

Locke

Spinoza

Montesquieu

Voltaire

Rousseau

Smith

Kant

Turgot

Burke

Priestley

Paine

Beccaria

Condorcet

Bentham

Korais

De Gouges

Wollstonecraft

Staël

Say

Humboldt

Constant

Ricardo

Guizot

List

Bastiat

Martineau

Emerson

Tocqueville

Mill

Spencer

Arnold

Acton

Weber

Hobhouse

Croce

Cassirer

Mises

Ortega

Keynes

Collingwood

Čapek

Hu

Hayek

Popper

Aron

Berlin

Friedman

Rawls

Sen

Nozick

Kymlicka

BadawiPoliticians

Jefferson

Kołłątaj

Madison

Artigas

Bolívar

Broglie

Lamartine

Macaulay

Kossuth

Deák

Cobden

Mazzini

Juárez

Lincoln

Gladstone

Cavour

Sarmiento

Mommsen

Naoroji

Itagaki

Levski

Kemal

Deakin

Milyukov

Lloyd George

Venizelos

Ståhlberg

Gokhale

Rathenau

Madero

Einaudi

King

Roosevelt

Pearson

Ohlin

Kennedy

JenkinsOrganisations

Africa Liberal Network

Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe

Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe Party

Arab Liberal Federation

Council of Asian Liberals and Democrats

European Democratic Party

European Liberal Youth

International Alliance of Libertarian Parties

International Federation of Liberal Youth

Liberal International

Liberal Network for Latin America

Liberal parties

Liberal South East European Network

Related topics

Anti-authoritarianism

Anti-communism

Bias in American academia

Bias in the media

Capitalism

Democratic

Centrism

Radical centrism

Economic freedom

Egalitarianism

Empiricism

Humanism

Individualism

Anarchist

Land value tax

Libertarianism

Left

Right

Pirate Party

Sexually liberal feminism

Utilitarianism

Liberalism Portal

Authority control databases International

FAST

ISNI

VIAF

WorldCat

National

Norway

Chile

Spain

France

BnF data

Argentina

Catalonia

Germany

Italy

Israel

Finland

Belgium

United States

Sweden

Latvia

Japan

Czech Republic

Australia

Greece

Korea

Croatia

Netherlands

Poland

Portugal

Vatican

Academics

CiNii

Artists

KulturNav

ULAN

People

Deutsche Biographie

Trove

Other

SNAC

IdRef